The Vault

CHAPTER 28 – WEATHERING A STORM OUT OF THE SOUTH

Posted on: Monday October 9, 2023

To purchase a copy of this book, simply click on the “books” tab on this website and follow the prompts.

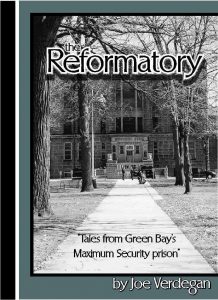

(The following is chapter 28 of the 2020 Amazon No. 1 best-selling book “The Reformatory – Tales From Green Bay’s maximum-security prison.” Sgt. John Verville, who tells his story of a disturbance in the prison’s South Cell Hall in 2002. Verville passed away in October, 2023 RIP Johnny V.)

Over the years there have been certain disturbances inside the walls that have changed people forever. John Verville readily admits one day as the sergeant in the South Cell Hall in 2002 was beyond life changing.

Verville, a native of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, was a utility sergeant. What that meant was that each day he’d be slotted into a different post throughout the institution. It could be filling in on another sergeant’s day off, vacation or what have you. On this particular day Verville’s post was the sergeant in the South Cell Hall.

“That day went actually fairly smoothly in the morning,” Verville recalled. “We had mostly inmates who were assigned to school in there, so we rang out three hours worth of school classes. The inmates came and went and we didn’t detect any problems at all.”

What Verville was completely unaware of (and would later that day be the impetus for a vicious attack on staff) was that the evening prior the inmates who resided in the South Cell Hall were denied showers and the chance to exchange their clothes and linen as was a weekly routine. Apparently, a mechanical breakdown resulted in no hot water and that’s why the showers were not run.

“There was nothing in the unit log book referring to it and no supervisor that day said one word to me or any other staff about anything,” Verville recalled. “What was about to happen in there completely blindsided everybody.”

When the cell halls fed lunch, half of the unit was rung out to feed at a time. That meant the frontside of all four tiers of inmates were out eating. That meant close to 200 inmates at one time were feeding all at once.

After inmates had been seated in the chow hall a staff member from a kitchen security observation booth would release the inmates by calling out one tier at a time. It’s a mundane, routine thing that was done three times a day, everyday, 365 days a year. The inmates were used to it. The staff were used to it.

The only problem was on this day when staff called out the first tier, nearly ALL those inmates got up, threw their lunch trays in the tray return, and hustled back to the cell hall. For many staff in the dining hall that day the hair stood up on the back of their collective necks.

“I had maybe a 30-second head start as to what was coming,” Verville recalled. “Somebody – I can’t remember who – called from that telephone at the tray return outside the dining hall and told me, ‘Something didn’t seem right,’ and ‘Almost everyone had gotten up and left.”

Verville, who was stationed at the sergeant’s desk near the entrance to the cell hall, turned and looked out into the rotunda and saw this huge group of inmates heading towards the cell hall.

“They weren’t violent or anything yet at that point, but they were moving fast and at first they appeared to be heading back to their cells,” Verville said. “At first, I thought maybe it wasn’t a good lunch or something like that. That would happen on occasion.”

Instead of locking their cell doors upon their return, the inmates all started coming back out of their cells, many of them holding their dirty clothing and other bedding. They soon swarmed the sergeant’s desk, surrounding it.

“The inmates were demanding showers and the opportunity to exchange their linens,” Verville said. “Right before that I had called over the radio and asked for some additional staff to respond to the South Cell Hall to assist with getting inmates to return to their cells. Sergeant Paul Habeck was in the control center that day and did a good job of helping to get the word out.”

A few more staff did show up, but the crowd of hostile inmates quickly grew. They became louder. Soon inmates from the upper tiers began tossing their bags of nasty clothing and laundry over the tier towards the sergeant’s desk.

“It was awful and some of the nasty things were thrown our way,” Verville recalled. “It was escalating quickly I was getting pelted with some absolutely nasty stuff.”

What didn’t help that day was Verville’s cell hall extra (sort of like a sergeant’s right-hand man or woman) Scott Pagel had taken what was called an “early out” that day and left. His replacement was utility officer Curt Flannery, a very dependable and capable replacement.

“I tried talking to those guys, but it was getting out of hand very quickly, so I called for a supervisor,” Verville recalled. “By this time there were at least 50 inmates surrounding the desk and a whole bunch more on the way down from all the tiers. The whole deal hit me like a ton of bricks. We had no warning whatsoever.”

A pair of captains came down, Steven Wellens and Dennis Natzke. Both had been there for a long time and had many years under their belts.

“I’ll never forget this because Wellens looked at those inmates and said to the hostile crowd, ‘If you guys don’t go back to your cells now – everyone is getting locked up!,” Verville recalled. “I thought to myself ‘You’re a supervisor! The last thing you should be doing is coming down into my cell hall and talking to an angry mob like that.’ Steve was normally a good supervisor but this was over the top.”

According to Verville, it was Wellens words that sparked the ensuing melee.

“I remember Steve (Wellens) had braces on at the time,” Verville said. “He got punched so hard in the face he went flying into this computer desk we had up against a wall. The blood was everywhere.”

Verville hit the fight alarm. An all-out attack on staff was ongoing.

“Staff were getting the piss beaten out of them everywhere I turned,” Verville said. “It didn’t matter if it was a male or a female staff member. These inmates were attacking everyone.”

One female who was knocked unconscious was Officer Kim Schauer.

“I saw little Kimmie Schauer get hit and she dropped to the floor like a slab or meat,” Verville recalled. “It was awful. We were outnumbered because there were well over 100 inmates involved in this and there were maybe one dozen staff who were able to respond. The odds were against us.”

Remember, as CO’s we didn’t carry guns on us. At that time most staff didn’t even have so much as pepper spray. You were equipped with handcuffs, a radio and your verbal skills and whatever training you had. That was it.

Officer Flannery, Verville’s extra that day in the block, was knocked out cold that day after being punched and kicked repeatedly by multiple inmates.

“I saw three guys who I will always have the utmost respect for because they got their asses kicked and kept getting back up and doing everything they could,” Verville said. “Three guys. Denis O’Neill, Steve Delorensi and Al Christensen. Those guys would not give up. The punches were being thrown back and forth. We were so outnumbered.”

Order was finally restored when staff came down with the projecto jets – a device that sprays crippling tear-gas like chemicals. “(The inmates) finally started scurrying like rats back into their cells after that,” Verville said. “Problem was I wasn’t a regular staff member down there, so it was tough for me to identify who these inmates were. And the camera system back then was really shitty.”

Once the donnybrook was under control, an emergency count took place.

“My concern was that a staff member didn’t get dragged into an inmate’s cell or something like that,” Verville said. “I refused to leave that cell hall until I knew that every blue shirt was accounted for.”

After the disturbance had been quelled, Verville decided to get out of the block for a few minutes and go downstairs into the breakroom to process what had just happened.

“They obviously fed the backside of the cell hall in their cells because we went on lockdown right away for several weeks after that,” Verville said. “I was walking through the gates to get downstairs and Paul Habeck opened the door to the control center and gave me a big hug. She told me how unbelievable of a job I did. It brought me to tears.”

Verville was relieved that day and didn’t return to the cell hall the rest of the day.

“And what really got me was they insisted that we get incident reports and conduct reports written right away,” Verville said. “In my opinion, it was something that could have waited until the next day. But that was the GBCI way.”

That day changed Verville forever.

“I went home and buried myself into a bottle,” Verville said. “I was an alcoholic and that deal just made it worse. But I had responded to inmate hangings before that. Suicides. Overdoses. None of that even came close to that day in the South Cell Hall. It changed me on how I conducted my business inside the walls after that.”

Verville admits he became a frequent sick leave abuser as the years went on and felt management had lost a lot of respect for him.

“Wellens never said a word to me after that incident,” Verville said. “Plus, there were so many new supervisors coming in from other prisons. They were young enough to be my daughters for God’s sake. That place was changing. GBCI was going downhill in my opinion. It was time to get the hell out of there.”

In 2015 Verville left Green Bay to go to the minimum camp at Sanger B. Powers. Verville later retired with 27 years of state service.

“If I hadn’t left Green Bay, I felt I would have gotten fired,” Verville admitted. “Working there was ten times worse than Sanger B. I have some regrets but to sum it up there were many poor decisions that led up to that fateful day in the South Cell Hall. It was the worse nightmare I could have imagined.”

Author Joe Verdegan spent nearly 27 years as a correctional officer, most of his career at GBCI. (Kim Verdegan photo)